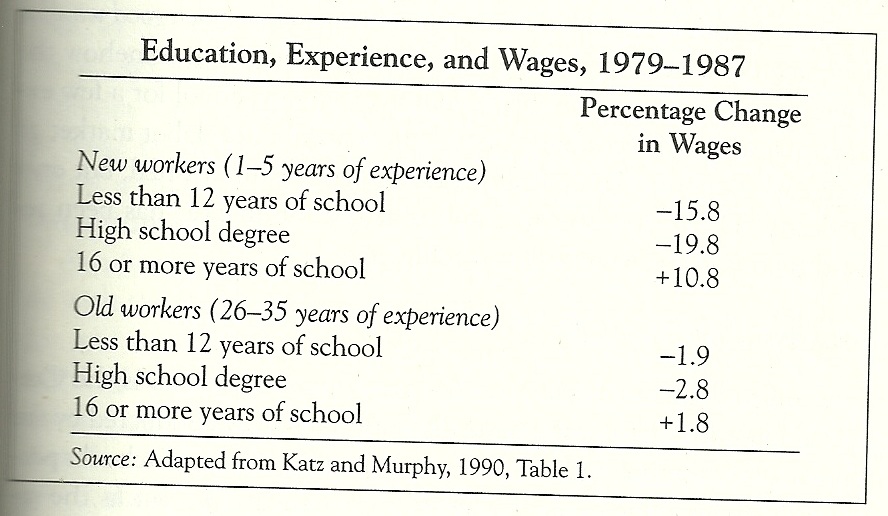

I’m reading “The Bell Curve” and am finding the book fascinating. As I mentioned in my previous post on this topic:

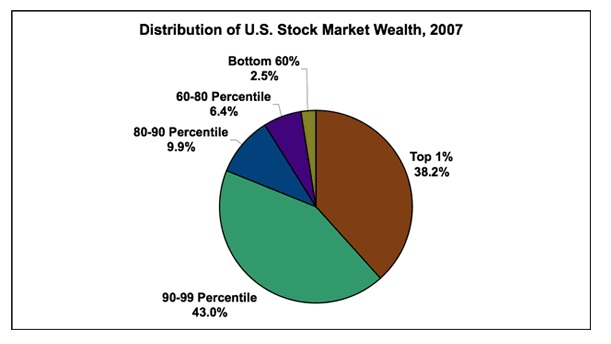

That attaining wealth is more and more becoming reserved for the pre-existing well to do’s.

For a long time I’ve fought this belief. I’ve fought the idea that America is not the land of opportunity. That we’ve somehow lost the idea that if you work hard enough you can do anything.

I’ve fought it.

And now I’m reading a book, The Bell Curve, and I’ve seen some interesting data. For example, it seems to be important where you come from if you wanna avoid poverty:

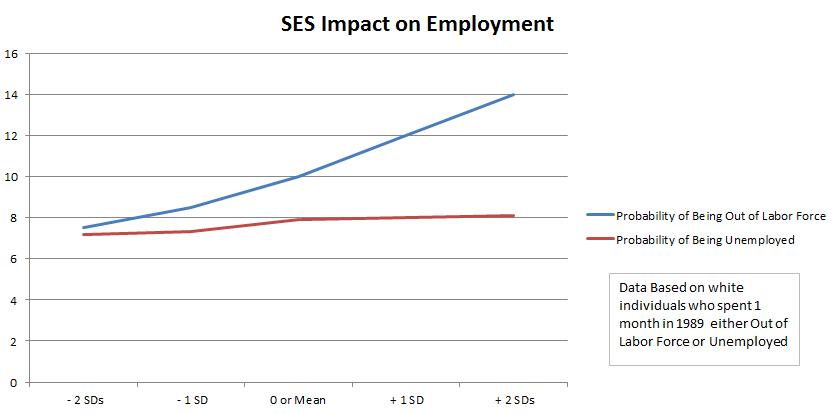

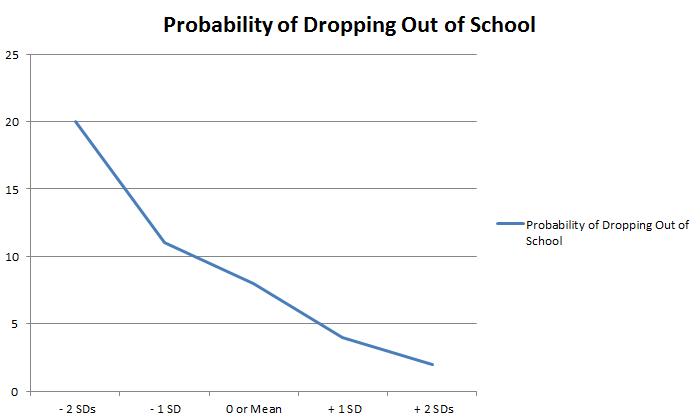

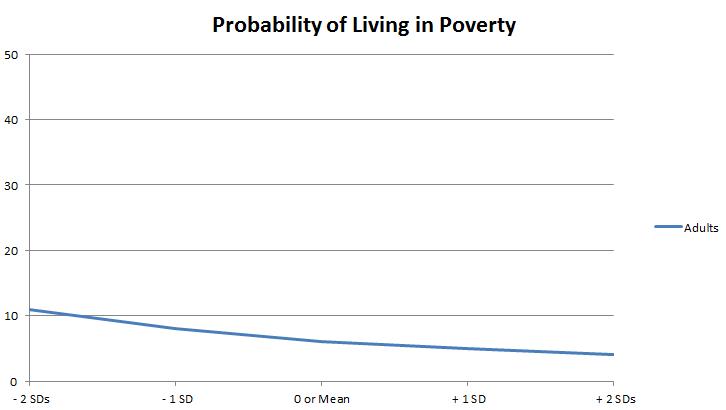

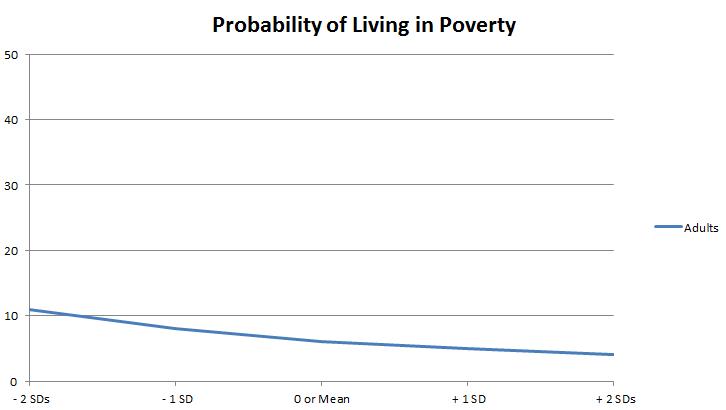

As I continue to make my way through the book, there is good data that reinforces the above statement. Namely, where you come from, or who you are born to, impacts where you will end up. Consider the white population:

I can only estimate the data above, the book doesn’t provide exact numbers, but you can see that as parental SES goes from 2 standard deviations below the mean to 2 standard deviations above the mean, the chance that an individual finds themselves in poverty is reduced. In fact, if you look at the numbers, the families at the far poor end of the scale have almost three times the chance to produce poor children than the very well off families at the other end.

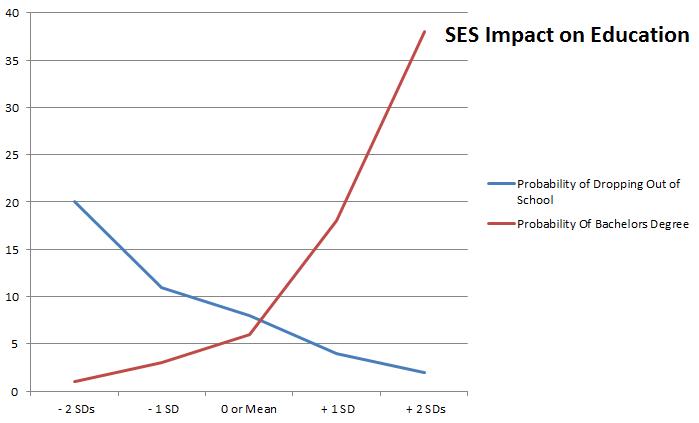

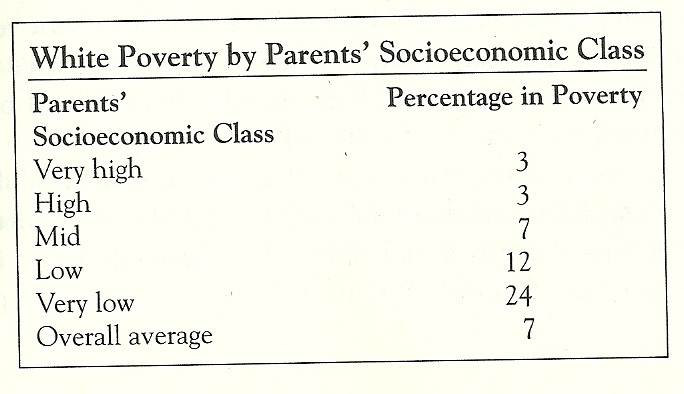

What if we dig deeper in the data? What happens if we look at the probability that a child lives in poverty? How does socioeconomic status impact that?

Well, it turns out that the data is divided. For example, consider married white mothers:

Interesting.

It turns out that that being a married mother helps reduce the chance of childhood poverty. Reduces but only slightly. However, what is interesting is that the impact of a higher socioeconomic parent is magnified. In the general public, a higher parental SES ranking meant that an adult had 1/3 the chance of ending up in poverty. For children, it’s much more dramatic.

For a child, having parents in the lowest SES class means that poverty is ~5.5 times as likely than if that child came from parents in the highest SES rankings. That is, kids from the most well of parents suffer poverty at rates of about 2%. Kids from the least well off suffer poverty at rates of about 11%.

Now for the shocker. Let’s look at single white mothers:

WOW!

Kids of white mothers that are either separated, divorced o r never married suffer massively higher rates of poverty than mothers of kids who are married. But again, for the sake of this specific conversation, the socioeconomic ranking of the parents is meaningful. Parents who rank at the very low end raise kids who have approximately a 39% chance of being in poverty. Mothers who are in the top ranks of socioeconomic ranking? Their kids only have about a 30% chance of living in poverty, almost a 33% less chance.

The data is hard to argue with. The “well off-ness” of the parents seems to have a powerful impact on the chance of poverty of a child.