The Middle Class.

What is it? Who is it? How do you get there, stay there or even leave there?

What does it mean to be Middle Class?

Some might define it literally:

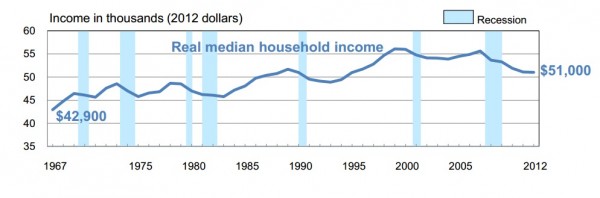

One helpful yardstick to judge whether you’re middle class: Median household income was $51,017 in 2012, according to the most recent U.S. census data. Robert Reich, a professor of Public Policy at the University of California-Berkeley and former Secretary of Labor, has suggested the middle class be defined as households making 50 percent higher and lower than the median, which would mean the average middle class annual income is $25,500 to $76,500.

If you’re in the middle of the middle, however – not lower or upper-middle class – that would be an income range between $39,764 and $64,582, says Aaron Pacitti, an assistant professor of economics at Siena College in Loudonville, N.Y.

Another such literal definition:

Financial Samurai Definition Of Middle Class: If you make within +/- 50% of your city’s household income for your age, you are middle class. For example, the average household income in San Francisco is $80,000. A person making $40,000 – $120,000 can comfortably consider himself or herself middle class. The cost of living in Des Moines, Iowa is obviously much lower, and the incomes will adjust accordingly. Income is only one part of wealth.

And finally a more descriptive definition:

The Middle Classes

Next come the middle classes, which make up the vast majority of the American population, and at the top of the middle class is the upper middle class, also known as the top of the class. Members of this class tend to be well educated, hold post-secondary degrees and have high-paying, white-collar positions. This class is male-dominated, and has an income of $100,000 or more annually. That’s enough to stay at the top one-third of U.S. incomes.In the middle of the middle classes is the lower middle class. This class usually has households with people who have a college education, but these people don’t have the degrees necessary to advance into higher-earning positions. This class contains lower-level, white-collar workers who generally earn between $32,500 and $60,000.

The lower middle class can be split into two different categories: the satisfied middle and the struggling middle. The satisfied middle can still find satisfaction and positivity in their lives, despite their modest incomes, and include a disproportionate amount of young and old, but no middle-aged adults. The struggling middle, however, contains households that actually earn “a lower median family income than Americans who put themselves on the lowest rungs of the social ladder,” and have a disproportionate amount of women and minorities, enabling them to have a lot in common with the lower class.

At the bottom of the middle classes is the working class, also known as the blue-collar class or as the anxious middle. This class is the most dissatisfied and downbeat of the middle classes, and don’t have as much education, meaning that they may have gone to college, but have more technical or vocational training. They are also usually paid by the hour, and have a variety of jobs, including: police officer, truck driver and factory worker. Salaries in this class fall between lower middle class and the poverty level, with a range of $23,050 to $32,500.

I suspect that 2015 and 2016 will bring about a large debate concerning the middle class. Elizabeth Warren is going to talk a WHOLE lot about the destruction of the middle class with very little work on defining it.

I’m interested. What IS the middle class?