I’m continuing my series on the chapters of “The Bell Curve”, by Herrnstein and Murray. If you are interested in the posts so far, just go to the category selections on the right sidebar, I’ve grouped them together under The Bell Curve.

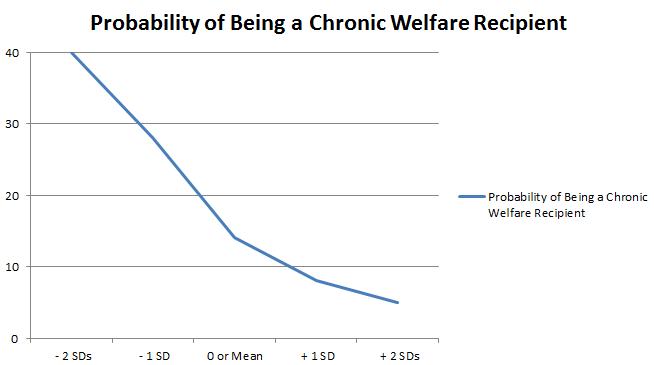

The other day we dealt with welfare and the impact that socioeconomic status has on:

- Going on it

- Staying on it

The results were mixed. The answer, it depends.

Today we’re gonna look at parenting and the impact of the SES of the mother on her children.

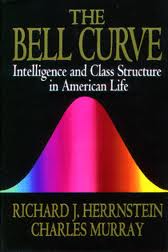

Even before the life of the child has a chance to take off, a critical component of parenting is the birth weight of that child. By examining the socioeconomic status of the mother we might catch a glimpse of it’s impact on her children:

As you can see from the chart the impact of the socioeconomic status of the mother is small or meaningless.

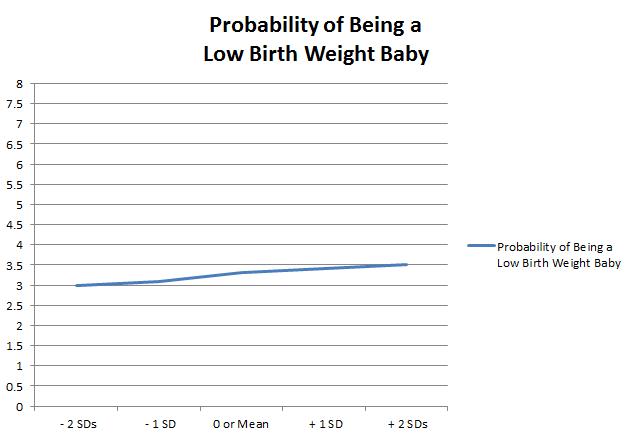

Moving to the early life of the child, the authors explore childhood poverty in the first three years of the child’s life. Again, holding other variables constant, the impact of the SES of the mother:

That impact is dramatic. Poor women raises poor kids while the wealthy mothers raise children above the poverty line. As soon as the mother’s wealth dropped below the average, the probability of childhood poverty rises very steeply.

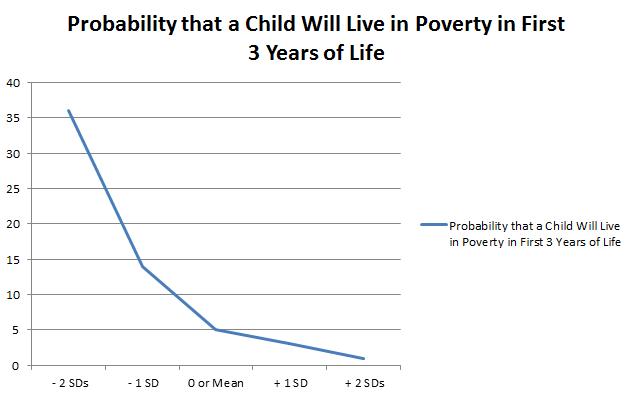

The next set of data describes the impact of the SES of the mother on the HOME index.

The Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) Inventory is designed to measure the quality and extent of stimulation available to a child in the home environment. The Infant/Toddler HOME Inventory (IT-HOME) comprises 45 items that provide information from the child’s perspective on stimuli found to affect children’s cognitive development. Assessors make observations during home visits when the child is awake and engaged in activities typical for that time of the day and conduct an interview with a parent or guardian. The IT-HOME is organized into six subscales: (1) Responsivity: the extent of responsiveness of the parent to the child; (2) Acceptance: parental acceptance of suboptimal behavior and avoidance of restriction and punishment; (3) Organization: including regularity and predictability of the environment; (4) Learning Materials: provision of appropriate play and learning materials; (5) Involvement: extent of parental involvement; and (6) Variety in daily stimulation. For the IT-HOME, 18 items are based on observation, 15 on interview, and 12 on either observation or interview.

In 1986, 1988 and 1990, the NLSY conducted surveys of the children and mothers using the HOME observations. From that data, the authors build a probability of scoring in the lowest decile of that index based on the SES of the mother:

Again we see the pattern. As the wealth of the mother decline, the HOME index score of the family unit becomes worse. Only 3 in 100 of the wealthiest women have children in the lowest decile in the index while the poorest women have 10 in 100.

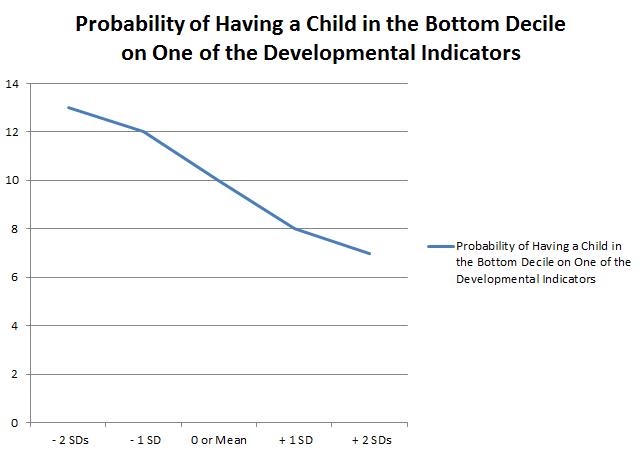

The next topic in the chapter deals with developmental outcomes of the children of moms in the NLSY. The study administered a host of tests regrading those outcomes. In short, the book is looking at measuring those children who scored in the bottom decile of the 4 indicators of a given test year. If they answered “yes” for any of the four tests being in that bottom decile or “no” if they did not.

The results holding all variables equal but SES of the mother:

The data is relatively modest; 5 points separate the top from the bottom.

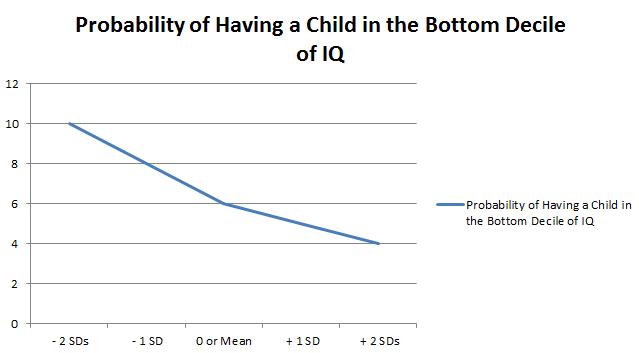

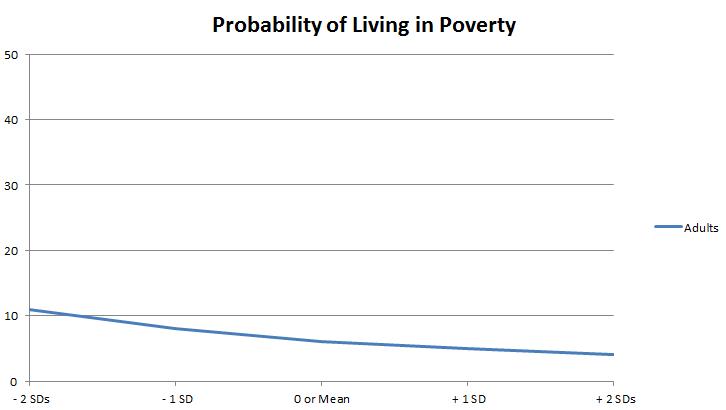

Finally, the last factor studied in the chapter – the IQ of the child. Here the authors again decided to look at the probability of the child ranking in the bottom DECILE of IQ based on the SES of the mother. Again, the data:

Again, the impact of the mother’s SES status is mild; moving the ranking from 10% to 4%, highest to lowest.

In conclusion, with the notable exception of living in poverty for the first 3 years of life, the SES of the child’s mother has only mild predictive value in the studied outcomes.